User:Alice/Special Issue V: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

Techno/Cyber/Xeno-Feminism | Techno/Cyber/Xeno-Feminism | ||

The Intimate and Possibly Subversive Relationship Between Women and Machines | The Intimate and Possibly Subversive Relationship Between Women and Machines | ||

[[File:Punch.png|right|300px]] | |||

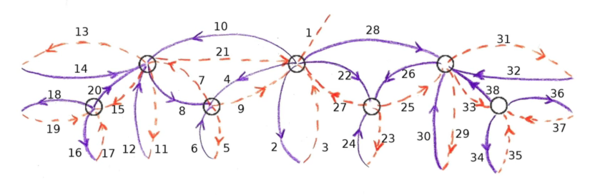

My reader explores topics from women's introduction into the technological workforce, the connection between weaving and programming, and using technology in favour of the feminist movement. One major concept that appears throughout the reader is an almost mystical connection between women and software writing, embedded deep in women's tradition of weaving not just threads, but networks. | |||

Following this thread [pun intended], I continued my research in the history of computing, which led me to the Jacquard loom, invented in 1804 by Joseph Jacquard. This mechanical loom worked with a deck of punch cards which controlled the pattern which the machine executed. This was the first instance of a programmable machine. Later on, Charles Babbage's Analytical Machine was designed to be able to perform all four arithmetic operations, with the use of a similar punch card system. This technique was further developed for the US census in 1890 by Herman Hollerith, whose company later became IBM. | |||

== Production == | == Production == | ||

[[File:Japanese.png|right|600px]] | |||

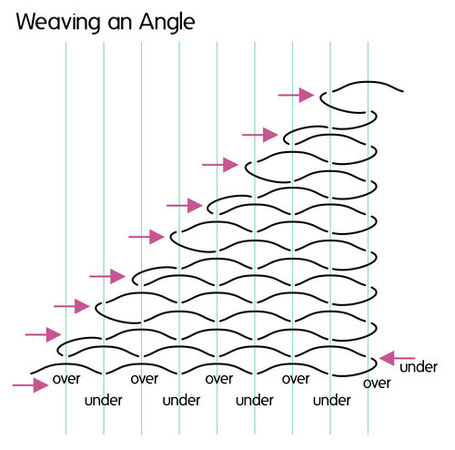

I built this reader using only free software. It was designed using HTML and CSS, compiled using Weasyprint, and the cover was designed in GIMP. The printing was done at WDKA. For binding, I decided to keep in line with the concept of weaving, and use Japanese binding with cotton thread. | I built this reader using only free software. It was designed using HTML and CSS, compiled using Weasyprint, and the cover was designed in GIMP. The printing was done at WDKA. For binding, I decided to keep in line with the concept of weaving, and use Japanese binding with cotton thread. | ||

=== Research === | === Research === | ||

Research questions: | Research questions: | ||

| Line 32: | Line 36: | ||

=== Software experiments === | === Software experiments === | ||

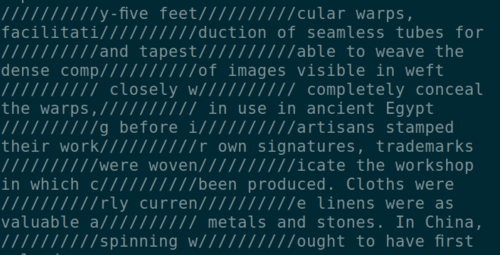

Exploring further the relationship between weaving and programming, I looked at the perceived similarities between the two. | Exploring further the relationship between weaving and programming, I looked at the perceived similarities between the two. | ||

For me, one of the best representations of this connection was through an equation: | |||

<code> | |||

'''input + rules = output''' | |||

</code> | |||

In the case of weaving, the input is thread, the rules are the pattern, and the output is fabric. In the case of software, the input is data, the rules are the sequence, syntax, etc, and the output is data modified according to the rules. In order for this connection to be stronger, it is necessary that anyone who analyzes the output and knows the available rules, can retrace all the steps that were taken in the process of weaving/programming. | |||

<gallery mode='packed' widths=300px heights=300px> | |||

File:Weaving_instructions.jpeg | |||

File:Weave.jpg | |||

File: | |||

</gallery> | |||

==Over/under== | |||

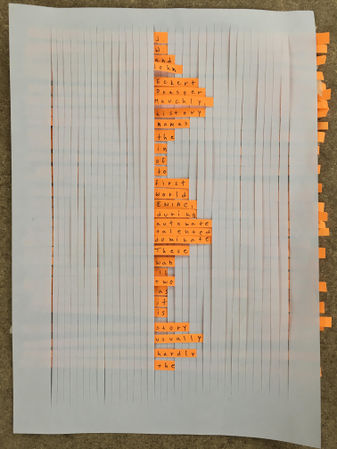

I wrote an interpreted programming language in Python that could receive as rules basic weaving instructions 'over' and 'under' and apply a pattern onto text, simulating a plain weave. | |||

For the command 'over', the pattern would show the respective characters as they are. For the command 'under', the respective characters would be replaced with an unicode character. | |||

First output: | First output: | ||

| Line 59: | Line 80: | ||

return splitted_cmds | return splitted_cmds | ||

def tokenize(s): | def tokenize(s): | ||

return s.split() | return s.split() | ||

| Line 75: | Line 95: | ||

line_number = 0 | line_number = 0 | ||

last_index = 0 | last_index = 0 | ||

def eval(cmds): | def eval(cmds): | ||

| Line 81: | Line 100: | ||

global line_number | global line_number | ||

global last_index | global last_index | ||

global pattern | |||

for cmd in cmds: | for cmd in cmds: | ||

| Line 88: | Line 108: | ||

elif cmd[0] == 'load': | elif cmd[0] == 'load': | ||

contents = open('output.txt').read() | contents = open('ocr/output.txt').read() | ||

text = textwrap.wrap(contents, 40, break_long_words=True) | text = textwrap.wrap(contents, 40, break_long_words=True) | ||

print('\n'.join(text)) | print('\n'.join(text)) | ||

| Line 120: | Line 140: | ||

print('\n'.join(pattern)) | print('\n'.join(pattern)) | ||

elif cmd[0] == 'save': | |||

pattern = text[0:line_number + 1] | |||

pattern_file = open('output/patternfile.txt', 'w') | |||

pattern_file.write('\n'.join(pattern)) | |||

pattern_file.close() | |||

print('Your pattern has been saved in the output folder.') | |||

elif cmd[0] == 'quit': | elif cmd[0] == 'quit': | ||

print(' | print('Come back soon!') | ||

raise LeavingProgram() | raise LeavingProgram() | ||

else: | else: | ||

joined = ' '.join(cmd) | joined = ' '.join(cmd) | ||

print('Did not understand command {}'.format(joined)) | print('Did not understand command {}'.format(joined)) | ||

if __name__ == '__main__': | if __name__ == '__main__': | ||

repl() | repl() | ||

<source> | <source> | ||

Revision as of 19:16, 25 March 2018

Reader #1

Title and topic

Techno/Cyber/Xeno-Feminism The Intimate and Possibly Subversive Relationship Between Women and Machines

My reader explores topics from women's introduction into the technological workforce, the connection between weaving and programming, and using technology in favour of the feminist movement. One major concept that appears throughout the reader is an almost mystical connection between women and software writing, embedded deep in women's tradition of weaving not just threads, but networks.

Following this thread [pun intended], I continued my research in the history of computing, which led me to the Jacquard loom, invented in 1804 by Joseph Jacquard. This mechanical loom worked with a deck of punch cards which controlled the pattern which the machine executed. This was the first instance of a programmable machine. Later on, Charles Babbage's Analytical Machine was designed to be able to perform all four arithmetic operations, with the use of a similar punch card system. This technique was further developed for the US census in 1890 by Herman Hollerith, whose company later became IBM.

Production

I built this reader using only free software. It was designed using HTML and CSS, compiled using Weasyprint, and the cover was designed in GIMP. The printing was done at WDKA. For binding, I decided to keep in line with the concept of weaving, and use Japanese binding with cotton thread.

Research

Research questions:

- Does software have a gender?

- What elements and concepts are revealed when exploring the connection between weaving and programming?

- How have women challenged the imbalance in gender representation in technology?

List of works

In order of appearance in the reader:

1. When Computers Were Women, Jennifer Light

2. The Future Looms, Sadie Plant

3. Zeros + Ones, Sadie Plant

4. A Cyborg Manifesto, Donna Haraway

5. Where Is the Feminism in Cyberfeminism?, Faith Wilding

6. 100 Anti-Theses, Old Boys Network

7. Xenofeminism: A politics for Alienation, Laboria Cuboniks

Software experiments

Exploring further the relationship between weaving and programming, I looked at the perceived similarities between the two. For me, one of the best representations of this connection was through an equation:

input + rules = output

In the case of weaving, the input is thread, the rules are the pattern, and the output is fabric. In the case of software, the input is data, the rules are the sequence, syntax, etc, and the output is data modified according to the rules. In order for this connection to be stronger, it is necessary that anyone who analyzes the output and knows the available rules, can retrace all the steps that were taken in the process of weaving/programming.

Over/under

I wrote an interpreted programming language in Python that could receive as rules basic weaving instructions 'over' and 'under' and apply a pattern onto text, simulating a plain weave. For the command 'over', the pattern would show the respective characters as they are. For the command 'under', the respective characters would be replaced with an unicode character. First output:

Second output:

Code

<source lang=python>

import linecache import textwrap import sys from sys import exit

class LeavingProgram(Exception):

pass

def parse(program):

cmds = program.split(',')

splitted_cmds = []

for cmd in cmds:

splitted = cmd.split()

splitted_cmds.append(splitted)

return splitted_cmds

def tokenize(s):

return s.split()

def repl():

while True:

try:

val = eval(parse(input('> ')))

if val is not None:

print(val)

except LeavingProgram:

break

text = None line_number = 0 last_index = 0

def eval(cmds):

global text global line_number global last_index global pattern

for cmd in cmds:

if cmd == []:

line_number += 1

last_index = 0

elif cmd[0] == 'load':

contents = open('ocr/output.txt').read()

text = textwrap.wrap(contents, 40, break_long_words=True)

print('\n'.join(text))

line_number = 0

last_index = 0

elif cmd[0] == 'show':

print(text[line_number])

elif cmd[0] == 'under':

current_line = text[line_number]

char_number = int(cmd[1]) - 1

char_list = list(current_line)

x=range(last_index, char_number + last_index + 1)

for time in x:

if time < len(char_list):

char_list[time] = u'\u21e2'

last_index += char_number + 1

joined = .join(char_list)

text[line_number] = joined

elif cmd[0] == 'over':

last_index += int(cmd[1])

elif cmd[0] == 'pattern':

pattern = text[0:line_number + 1]

print('\n'.join(pattern))

elif cmd[0] == 'save':

pattern = text[0:line_number + 1]

pattern_file = open('output/patternfile.txt', 'w')

pattern_file.write('\n'.join(pattern))

pattern_file.close()

print('Your pattern has been saved in the output folder.')

elif cmd[0] == 'quit':

print('Come back soon!')

raise LeavingProgram()

else:

joined = ' '.join(cmd)

print('Did not understand command {}'.format(joined))

if __name__ == '__main__':

repl()

<source>