Thematic-History of Avantgarde Cinema: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "== Lens-Based Thematic Project Seminar 2016- 2017 == === Thematic Project Seminar 3: ‘A brief survey of history of Avantgarde Cinema and its relevance for your artistic prac...") |

|||

| (4 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== Lens-Based Thematic Project Seminar | == Lens-Based Thematic Project Seminar 2017- 2018 == | ||

=== Thematic Project Seminar 3: ‘A brief survey of history of Avantgarde Cinema and its relevance for your artistic practice’, | === Thematic Project Seminar 3: ‘A brief survey of history of Avantgarde Cinema and its relevance for your artistic practice’, lead by Anna Abrahams === | ||

'''Monday 8 Jan: Cinema celebrates the Machine Age (Futurism, Constructivism, Bauhaus)''' <br/> | |||

In the 1910’s, the futurists called for an art that glorified speed and violence, one that above all reflected the dynamism of the machine age. Outrage and irony were their motors. Film was the medium that came closest to these artistic ideals - but they made only a handful of them. The only surviving film related to Italian Futurism: is Thais, made in 1916 by Futurist photographer Anton Giulio Bragaglia with the collaboration of Futurist set designer Enrico Prampolini. | In the 1910’s, the futurists called for an art that glorified speed and violence, one that above all reflected the dynamism of the machine age. Outrage and irony were their motors. Film was the medium that came closest to these artistic ideals - but they made only a handful of them. The only surviving film related to Italian Futurism: is Thais, made in 1916 by Futurist photographer Anton Giulio Bragaglia with the collaboration of Futurist set designer Enrico Prampolini. | ||

| Line 11: | Line 9: | ||

Between 1919 and 1933 the Bauhaus in the German towns of Weimar and Dessau was a world-famous training ground for aspiring designers and artists who were being steeped in modernist theory. Art and design merged in a revolutionary view on Gestaltung: the idea was to develop new forms for the new citizen in a new (and socialist) world. In addition to constructivist photography, the Bauhaus also focused on the pre-eminent modernist medium of the 1920s: film. | Between 1919 and 1933 the Bauhaus in the German towns of Weimar and Dessau was a world-famous training ground for aspiring designers and artists who were being steeped in modernist theory. Art and design merged in a revolutionary view on Gestaltung: the idea was to develop new forms for the new citizen in a new (and socialist) world. In addition to constructivist photography, the Bauhaus also focused on the pre-eminent modernist medium of the 1920s: film. | ||

''' | '''Monday 22 Jan: Cinema as the road to the irrational (dada and surrealism)''' <br/> | ||

''' | [[File:emak_bakia.png|250px|thumb|right|Emak Bakia (1927) by Man Ray]] | ||

On Friday 5 February 2016 it is a 101 years ago to the day that Cabaret Voltaire first opened its doors on Zürich’s Spiegelgasse, an event that marked the beginning of Dadaism and changed our view of art significantly. When the penniless poet and philosopher Hugo Ball opened Cabaret Voltaire with his companion Emmy Hennings in a café on 1, Spiegelgasse in Zürich, the First World War was at a tragic height. Together with Marcel Janco, Richard Huelsenbeck, Tristan Tzara, Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber Arp, Ball and Hennings protested against the insanity of the war by presenting ‘alogic’, absurd imagination and magic on stage under the name of Dada. | On Friday 5 February 2016 it is a 101 years ago to the day that Cabaret Voltaire first opened its doors on Zürich’s Spiegelgasse, an event that marked the beginning of Dadaism and changed our view of art significantly. When the penniless poet and philosopher Hugo Ball opened Cabaret Voltaire with his companion Emmy Hennings in a café on 1, Spiegelgasse in Zürich, the First World War was at a tragic height. Together with Marcel Janco, Richard Huelsenbeck, Tristan Tzara, Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber Arp, Ball and Hennings protested against the insanity of the war by presenting ‘alogic’, absurd imagination and magic on stage under the name of Dada. | ||

The performances left the audiences stunned as they were confronted with bruitist sound effects, modern dance, sound poetry, collages of word and image, negro masks or angular modernist improvisations on the piano. The shows provoked both indignation and rage among the audience and the air was often filled with hoots and catcalls. | The performances left the audiences stunned as they were confronted with bruitist sound effects, modern dance, sound poetry, collages of word and image, negro masks or angular modernist improvisations on the piano. The shows provoked both indignation and rage among the audience and the air was often filled with hoots and catcalls. | ||

| Line 19: | Line 17: | ||

What interested the surrealists was the developing of methods to liberate imagination from false rationality, restrictive customs and structures, and to understand the actual functioning of thought, first through the “pure psychic automatism” of writing and later through other media such as painting, film, theatre. This “unrational” approach allowed the artist to express unconventional ideas and to critique the current, unbearable conditions and habits of society. | What interested the surrealists was the developing of methods to liberate imagination from false rationality, restrictive customs and structures, and to understand the actual functioning of thought, first through the “pure psychic automatism” of writing and later through other media such as painting, film, theatre. This “unrational” approach allowed the artist to express unconventional ideas and to critique the current, unbearable conditions and habits of society. | ||

''' | '''Monday 12 Feb: American Underground –against the current of Hollywood ''' <br/> | ||

Mainstream cinema is reasonable and reassuring. Underground puts all values of Hollywood upside down. As a reaction to the smoothness of pop culture and the world of advertising, it dives into the dark world of passions, the elusive and the irrational. Underground cinema is like the Greek Dionysus cult - named after the god of wine, where the intoxication, the irrational, debauchery and sexuality are celebrated. In the US in the 60-ies the adagio was: Get your kicks before the whole shithouse goes up in Flames (Jim Morrison). Everything revolved around the feeling of NOW. | Mainstream cinema is reasonable and reassuring. Underground puts all values of Hollywood upside down. As a reaction to the smoothness of pop culture and the world of advertising, it dives into the dark world of passions, the elusive and the irrational. Underground cinema is like the Greek Dionysus cult - named after the god of wine, where the intoxication, the irrational, debauchery and sexuality are celebrated. In the US in the 60-ies the adagio was: Get your kicks before the whole shithouse goes up in Flames (Jim Morrison). Everything revolved around the feeling of NOW. | ||

American Underground was fed by European filmmakers who fled from war and repression in Europe in the first half of the 20th century. Combine this with the self-consciousness of the American artists of the forties and fifties (Beat Poets, New American journalism, abstract expressionism), good communication possibilities, a lot of talent and you have the perfect conditions for a new movement. | American Underground was fed by European filmmakers who fled from war and repression in Europe in the first half of the 20th century. Combine this with the self-consciousness of the American artists of the forties and fifties (Beat Poets, New American journalism, abstract expressionism), good communication possibilities, a lot of talent and you have the perfect conditions for a new movement. | ||

With works by: Andy Warhol, Kenneth Anger, Stan Brakhage, Shirley Clarke, Willard Maas, Mary Menken, Maya Deren, Jonas Mekas. | With works by: Andy Warhol, Kenneth Anger, Stan Brakhage, Shirley Clarke, Willard Maas, Mary Menken, Maya Deren, Jonas Mekas. | ||

'''Lecturer: ANNA ABRAHAMS | '''Lecturer: ANNA ABRAHAMS ''' <br/> | ||

''' | Anna Abrahams (Oslo, 1963) studied film theory at the University of Amsterdam. Abrahams produces, directs and edits films for the independent production foundation Rongwrong, which she founded with filmmaker Jan Frederik Groot in 1989. Abrahams is programmer avant garde and artist film for EYE Film Institute Netherlands and lectures at the Royal Academy of the Arts in The Hague. She is(co)author of ‘Warhol Films’, ‘ Oh, this is Fabulous’, ‘mm2. Experimental Film in the Netherlands’ and ‘film³ [kyü-bik film]’). | ||

Anna Abrahams (Oslo, 1963) studied | |||

'''Selection of films | '''Selection of films | ||

Latest revision as of 10:12, 30 November 2017

Lens-Based Thematic Project Seminar 2017- 2018

Thematic Project Seminar 3: ‘A brief survey of history of Avantgarde Cinema and its relevance for your artistic practice’, lead by Anna Abrahams

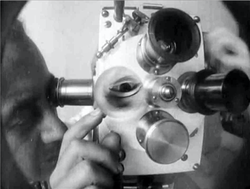

Monday 8 Jan: Cinema celebrates the Machine Age (Futurism, Constructivism, Bauhaus)

In the 1910’s, the futurists called for an art that glorified speed and violence, one that above all reflected the dynamism of the machine age. Outrage and irony were their motors. Film was the medium that came closest to these artistic ideals - but they made only a handful of them. The only surviving film related to Italian Futurism: is Thais, made in 1916 by Futurist photographer Anton Giulio Bragaglia with the collaboration of Futurist set designer Enrico Prampolini.

Around the same time in the USSR constructivism bloomed. Art, and cinema were inspired by the machine, that would liberate the people from slavery. One of the unforgettable films from that period is the science fiction film Aelita (Queen of Mars) (Yakov Protazanov, 1924).

Between 1919 and 1933 the Bauhaus in the German towns of Weimar and Dessau was a world-famous training ground for aspiring designers and artists who were being steeped in modernist theory. Art and design merged in a revolutionary view on Gestaltung: the idea was to develop new forms for the new citizen in a new (and socialist) world. In addition to constructivist photography, the Bauhaus also focused on the pre-eminent modernist medium of the 1920s: film.

Monday 22 Jan: Cinema as the road to the irrational (dada and surrealism)

On Friday 5 February 2016 it is a 101 years ago to the day that Cabaret Voltaire first opened its doors on Zürich’s Spiegelgasse, an event that marked the beginning of Dadaism and changed our view of art significantly. When the penniless poet and philosopher Hugo Ball opened Cabaret Voltaire with his companion Emmy Hennings in a café on 1, Spiegelgasse in Zürich, the First World War was at a tragic height. Together with Marcel Janco, Richard Huelsenbeck, Tristan Tzara, Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber Arp, Ball and Hennings protested against the insanity of the war by presenting ‘alogic’, absurd imagination and magic on stage under the name of Dada. The performances left the audiences stunned as they were confronted with bruitist sound effects, modern dance, sound poetry, collages of word and image, negro masks or angular modernist improvisations on the piano. The shows provoked both indignation and rage among the audience and the air was often filled with hoots and catcalls.

In Paris Dada evolved into a new avantgarde: surrealism.The exposing of the subconscious, the portraying of a dreamworld: for the Surrealists the 'seventh art' offered great potential. One of them was Luis Buñuel, director of classics like Un Chien Andalou and, L'âge d'or.. What interested the surrealists was the developing of methods to liberate imagination from false rationality, restrictive customs and structures, and to understand the actual functioning of thought, first through the “pure psychic automatism” of writing and later through other media such as painting, film, theatre. This “unrational” approach allowed the artist to express unconventional ideas and to critique the current, unbearable conditions and habits of society.

Monday 12 Feb: American Underground –against the current of Hollywood

Mainstream cinema is reasonable and reassuring. Underground puts all values of Hollywood upside down. As a reaction to the smoothness of pop culture and the world of advertising, it dives into the dark world of passions, the elusive and the irrational. Underground cinema is like the Greek Dionysus cult - named after the god of wine, where the intoxication, the irrational, debauchery and sexuality are celebrated. In the US in the 60-ies the adagio was: Get your kicks before the whole shithouse goes up in Flames (Jim Morrison). Everything revolved around the feeling of NOW.

American Underground was fed by European filmmakers who fled from war and repression in Europe in the first half of the 20th century. Combine this with the self-consciousness of the American artists of the forties and fifties (Beat Poets, New American journalism, abstract expressionism), good communication possibilities, a lot of talent and you have the perfect conditions for a new movement.

With works by: Andy Warhol, Kenneth Anger, Stan Brakhage, Shirley Clarke, Willard Maas, Mary Menken, Maya Deren, Jonas Mekas.

Lecturer: ANNA ABRAHAMS

Anna Abrahams (Oslo, 1963) studied film theory at the University of Amsterdam. Abrahams produces, directs and edits films for the independent production foundation Rongwrong, which she founded with filmmaker Jan Frederik Groot in 1989. Abrahams is programmer avant garde and artist film for EYE Film Institute Netherlands and lectures at the Royal Academy of the Arts in The Hague. She is(co)author of ‘Warhol Films’, ‘ Oh, this is Fabulous’, ‘mm2. Experimental Film in the Netherlands’ and ‘film³ [kyü-bik film]’).

Selection of films

- 7 Peaks, 2012, 35mm, 23 min.

- Desert 79°. Three Journeys Beyond the Known World, 2010, 35mm, 19 min.

- DIY (co-director Jan Frederik Groot), 2009, HDcam, 8 min.

- 5 Walks. Hercynia Silva, 2008, 35mm, 15 min.

- Cadavre Exquis, 2004, 16mm, 36 min.

- Rowing (co-director Jan Frederik Groot), 2003, 35mm, 1 min.

- Resort (co-director Jan Frederik Groot), 2002, 16mm, 15 min.

- Grave in the Tropics, 1998, 35mm, 45 min.

- Notes from the Underground, 1998, 16mm, 30 min.

- Sotsgorod. Cities for Utopia, 1995, 16mm, 92 min.