User:Sara/: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

The last script didn’t work on the ISIS video of the execution of Muath El-Kasasbeh. The camera needed to be fixed; the shot, stable. However, the slow transitions between appearance and disappearnace made me feel both enjoyment and confusion. I couldn’t tell if people existed or will exist, unless I compared the source video with the resulting one. Or rather, only their immoboilty would reveal them. I would like to try to acheive the same or a similar experience when working with ISIS videos. Would it be possible to turn them into beautiful tranquil and untroubled desert landscapes? (I will work on a still image using photoshop, to start with, and will try to either add it here in the coming couple of days, or show it on Monday along with the rest of the vidoe materials). | The last script didn’t work on the ISIS video of the execution of Muath El-Kasasbeh. The camera needed to be fixed; the shot, stable. However, the slow transitions between appearance and disappearnace made me feel both enjoyment and confusion. I couldn’t tell if people existed or will exist, unless I compared the source video with the resulting one. Or rather, only their immoboilty would reveal them. I would like to try to acheive the same or a similar experience when working with ISIS videos. Would it be possible to turn them into beautiful tranquil and untroubled desert landscapes? (I will work on a still image using photoshop, to start with, and will try to either add it here in the coming couple of days, or show it on Monday along with the rest of the vidoe materials). | ||

[[File:Disapp. | [[File:Disapp.png|center]] | ||

'''Hypervisibility''' (context) | '''Hypervisibility''' (context) | ||

Revision as of 19:19, 11 December 2016

(Re)visiting

The first time I mentioned the execution of the Jordanian pilot, Muath Safi Yousef Al-Kasasbeh, by the Islamic State (January, 2015), I was describing the shot values of the video, from one cut to the other. I thought that by not recounting the event of the execution itself, I would be sparing whomever is listening to me, the shocking horror of the violent account. I didn’t understand back then what to do with that or where to take it. I didn’t know what my question was either. Today, a year later, I unintentionally find myself revisiting that video again.

I started with wanting to transform the video into an excavation site, where I can deconstruct the contents of the image and strip it back to what it really is: calculable detectable digital data. In the research process, I stumbled upon opencv (open-source computer vision).

Observation 1:

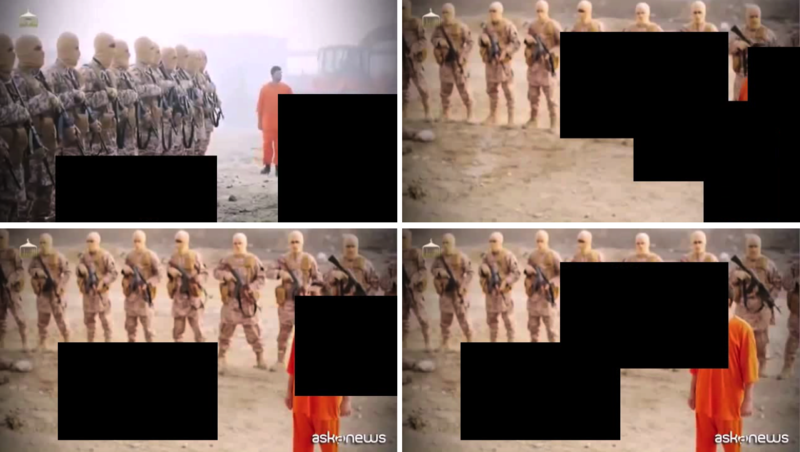

With Michael’s help, the first experiment conducted on the video of pilot Al-Kasasbeh was the frontal face recognition technique. It was interesting to see how a human face is perceived and understood by the algorithm. The script’s success as well as its failures in detecting both the pilot’s and the militants faces caught my attention. The algorithm managed to successfully detect the pilot’s face throughout the video. It has also managed to find tiny symmetrical face-resembling shapes or shadows present in the sand or in the rubble, but not a single time did the algorithm meet a militant’s eyes.

Observation 2:

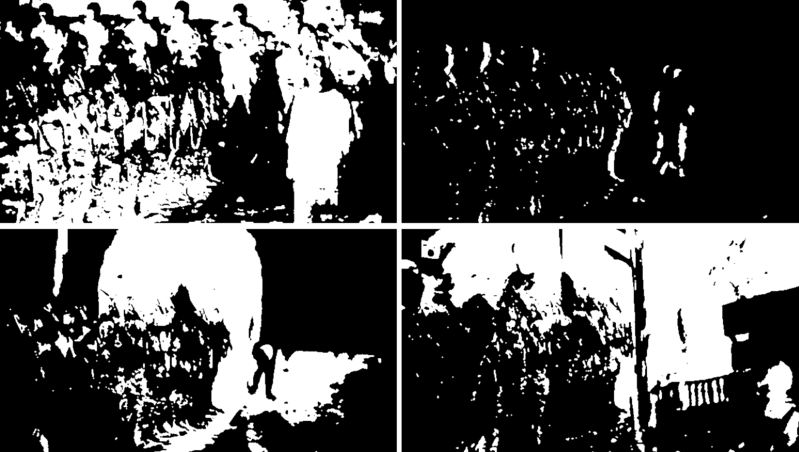

Hoping to separate the background from all human activity showing in the video, I started a new experiment. The background, with its hazy desert views and the blurry objects appearing vaguely, is reminiscent of mystery video games like Limbo. At the beginning of the game, a small boy appears lost in a dark black & white hazy forest called the “edge of hell". Trying to find his way through, the boy keeps encountering the most horrific deaths. He comes back to life endlessly. Like Limbo, the execution video starts with Muath entering the frame, walking, looking around, lost. Once background extraction is applied to the video, a black&white image appears. As the script takes the first frame as a reference for subtraction, the silhouette of the line of soldiers waiting for Muath at the beginning keeps recurring continously throughout the video. I didn’t manage to separate. I unknowingly merged.

Observation 3:

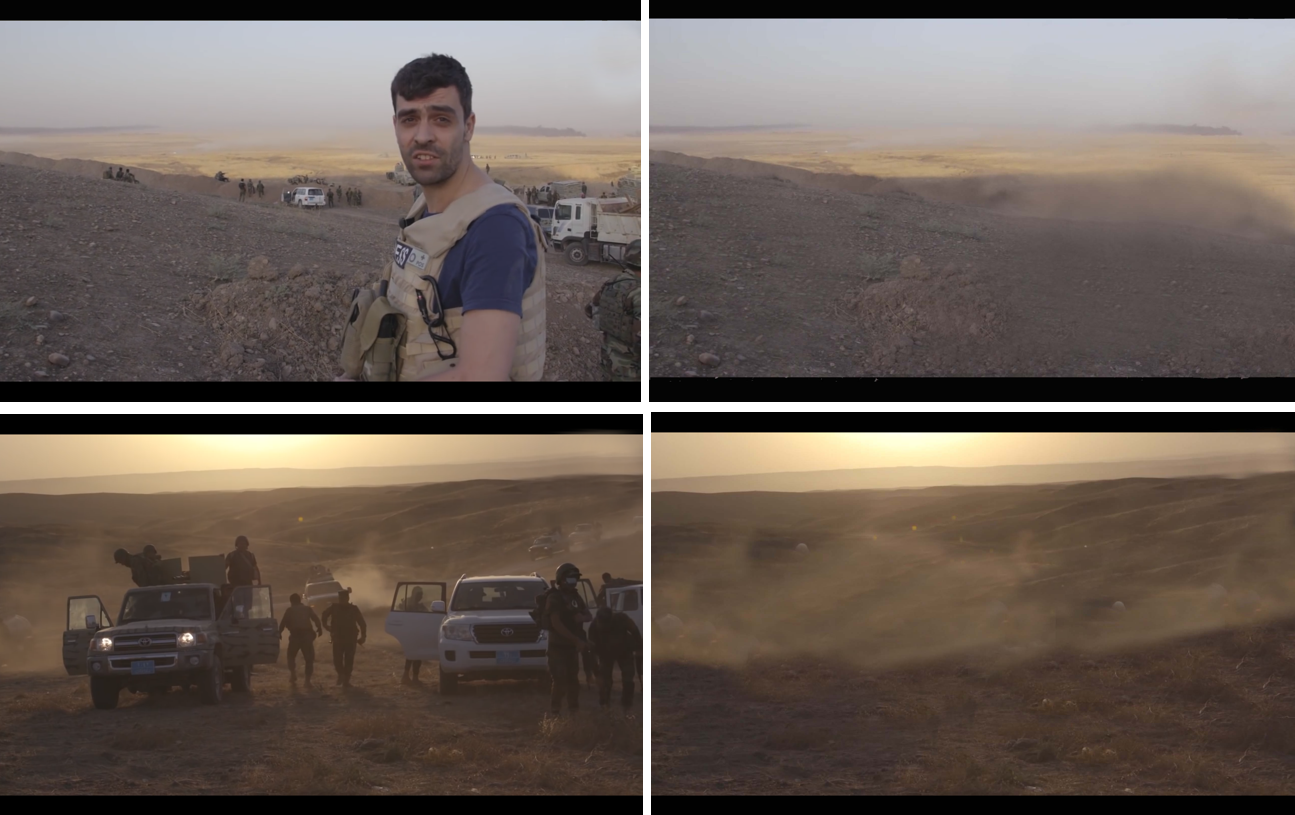

Still looking for a way to separate, I changed strategy. Still tinkering with opencv, I chose to diverge from the ISIS video. Maybe the problem was not in the script I was working with. Perhaps it was the violence itself that kept resisting my attempts. This time I looked for the mundane everyday ritual: traffic. I tried to extract the background using the function cv2.accumulateWeighted(). Here, each frame is fed into the function as a potential reference background, and the function keeps finding the averages of all frames fed to it, resulting in the following images (I will show the actual video on Monday, perhaps with different source material). In this video, objects and people are visible when immobile, but then they slowly vanish as they move. Their activity sentences them to disappearance.

Disappearance:

The last script didn’t work on the ISIS video of the execution of Muath El-Kasasbeh. The camera needed to be fixed; the shot, stable. However, the slow transitions between appearance and disappearnace made me feel both enjoyment and confusion. I couldn’t tell if people existed or will exist, unless I compared the source video with the resulting one. Or rather, only their immoboilty would reveal them. I would like to try to acheive the same or a similar experience when working with ISIS videos. Would it be possible to turn them into beautiful tranquil and untroubled desert landscapes? (I will work on a still image using photoshop, to start with, and will try to either add it here in the coming couple of days, or show it on Monday along with the rest of the vidoe materials).

Hypervisibility (context)

On the 29th of June 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and Sham (ISIS) released the very first recording online claiming an all-embracing Muslim Caliphate. The general sentiments accompanying this first declaration (at least for us living within the frontiers of the so-called Middle-East) were disbelief, then horror, then a surprising and brutal sense of familiarity. The Islamic State had already realized itself as a de facto sovereignty, performing its statehood in a simple matter of fact.

Despite international outrage, and with the absence of any recognition or support from intergovernmental organizations, the Islamic State perfromed its sovereignty, transgressesing the borders of national institutions, and taking the universal citizen, separated from community, nation or history, as its subject. The horrifying images that surfaced on the Internet after the declaration of the formation of the state drew my attention to the ease with which such scenes are iterated. The shocking casualeness of the image of a ravaged body circulating online turns suffering into a benumbing spectacle. This economy of what Saidiya Hartman calls hypervisibilty, problematizes the precariousness of empathy: the idea that we the only feelings that consume us as either indifference or narcissistic identification with the (humanity) of the other. It obscures a routinized violent quotidian embedded in the brutal familiarity of the everyday ritual. Hartman’s fundamental work animates within the context of slavery and the history of blackness. However, I hope that her determination to defamiliarize the familiar act as a methodoligical guide to my work.

Defamiliarizing the familiar (methodology)

“ […] A digital image that can be seen cannot be merely exhibited or copied but always only staged or performed. Here, an image begins to function like a piece of music, whose score, as is generally known, is not identical to the piece - the score being not audible, but silent. For the music to resound, it has to be performed. To perform something, however, means to interpret it, betray it, destroy it. Every performance is an interpretation and every interpretation is a misuse. "

As I remembered the description I made of the video of the execution of the Jordanian pilot last year, I became aware, through Hartman’s eyes, of the inevitability of the (re)production of the violent account. Even when I decided not to show the execution video (which is online nonetheless), I was still referring to it. The visual performance at the scene of violence inflicted on Math Al-Kasasbeh’s death was being restaged in all its different guises: in the performance of the digital image and the familiarity of my recounting it. Could I open up a space for this concern in my work?