User:Silviolorusso/research-method/nondigitalcybernetics

Tangible Networks: A non-digital journey into cybernetics

"We become the codes we punch" (Hayles, p. 46)

Abstract

Since the '50s, the cybernetic metaphor extended way beyond the borders of technology. It radically affected and reshaped the common interpretation of society, environment and mind. Putting computers aside, there are several artifacts that keep trace of this transformation.

Through a close observation of these, it is possible to identify the values that the cybernetic metaphor had assumed from time to time: propeller for collaborative practices, symbol of alienation and dehumanization, model for an extended community spirit and instrument of revolt against the dominant hierarchies. In particular, the research focuses on three different artifacts over about ten years (1964-1974):

- punch cards subverted by the Free Speech Movement

- the Whole Earth Catalog

- Radical Software magazine

The punch card and the human being

The history of punch cards by far precedes the advent of cybernetics and computers: the oldest ones date back to the first half of the eighteenth century. However it's only in 1890 that Herman Hollerith began to employ punch cards as devices to store data that are meant to be read by a machine. Punch cards brought large advantage to the American federal government by making the 1890 census' process faster and easier.

Over the following decades their use became widespread also among private companies: thus they started to send punch cards themselves as bills. At the same time, computer and cybernetics were invading the imagery of the population, causing a mix of fascination and anxiety. Consequently punched cards took on a negative symbolic value: they suggested hyper-rationality, dehumanization and conformity. Mirrored in the punch cards, people saw themselves as mere numbers.

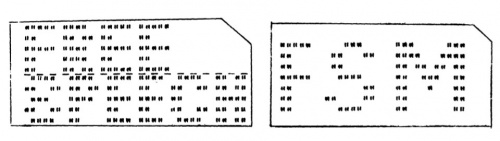

This vision became explicit at Berkeley -where punch cards were used to keep track of students' registrations and marks- through the protests of the “Free Speech Movement” that exploded in 1964. The target of the critics was in first place university itself, seen as a “knowledge factory”, where “no deviations from the norms are tolerated” (Lubar, p. 46). “Do Not Fold, Spindle of Mutilate” -the warning printed on the cards- became both a slogan in defense of the students and the inspiration to subvert these symbols of bureaucratization. Some students began to wear the cards as a sort of technical equivalent for soldier tags of prisoners' codes. Others went further, burning their own cards in order to express their freedom.

But the most interesting subversions of the punch cards regarded the technical appropriation or conversion. The students showed their technical control over the machine punching textual obscenities into some of the cards and then mixing them up with the official ones. Technical conversion was carried out punching holes in the shape of letters. Composing such words as “strike” or “free speech”, protesters developed a way to stage the contrast between human and machine through visual aspects of language.

After more than fifty years, this controversial relationship finds new facets. Universally adopted as a tool to discern humans from bots, CAPTCHA -acronym that stands for Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart- consists of a series of alphabetic glyphs that have undergone various distortions generated by a computer. In this way the user is asked to face a problem that the machine cannot solve and spam is prevented.

For the protest movement of the '60s punch cards were a symbol of alienation, therefore the usage conversion to a system of signs understood by human beings was an act of revenge. On the contrary, CAPTCHA's function is as mean of access to the machine. The machine is now the one who judge the human nature of the user, which relates to it performing a mechanical process. There is neither ideological nor political claim in this action, it only works as a device for identification. However the circumventions of this system show how the distinction between man and machine may lead to paradoxical outcomes. Cheap labour from developing countries is hired by spammers to solve big amounts of CAPTCHA's. The visual outcome of a system of signs therefore appears as a borderline between machine and human being. Within the process of addressing the diversity between the two, their relationship is redefined and reinforced, both in a symbolic and procedural way.

The Whole Earth Catalog as a focused search-engine

As seen with the Free Speech Movement and punch cards, cybernetics and its technologically related devices represented for a certain period the absolute absence of individuality and the dull standardization driven by the dominant power. Actually the environments in which cybernetics found its early applications -big university laboratories such as the Rad Lab in the MIT- were characterized by an opposite approach. Over the 50's and the 60's, the premises of cybernetics and systems theory encouraged a new model for collaborative practices, a rhetorical tool for connecting different disciplinary fields and even an encompassing reading of the whole earth as a system of systems. From this point of view, the individual -a system in itself- had the possibility to improve his own context and positively see himself as a node in a series of networks (Turner).

Paradoxically, these ideas developed at the core of the academic-military-industrial complex were afterwards merged into the philosophy of the counterculture, which was refusing or even fighting against the technocratic bureaucracy. Certainly the systems theorist and inventor Buckminster Fuller became a key figure in the bridging of this two opposite worlds, because of his reinterpretation of cybernetics in ecological terms. He demanded for a host of “Comprehensive Designers”, scientists able to exceed their disciplinary boundaries and act according to a global vision of the “Spaceship Earth”. The role of the technology, even the one developed by hierarchic powers, was supposed to be considered as a tool for social transformation.

Meanwhile, art collectives such USCO (The Company of Us) were employing projectors, stoboscopes, and other devices in their heappenings, mixing technology and misticism. Another group called the Merry Pranksters, whose mentor was the writer Ken Kesey, referred to cybernetics through collective experiences, often induced by LSD.

A young biologist called Stewart Brand was both member of the Merry Pranksters and in close contact with USCO; he deeply studied systems theory and he refused the cold war's hyper-rational atmosphere, like the students of the Free Speech Movement previously did. Stewart Brand was profoundly fascinated by technology but at the same time he visited the Indian reservations and the counterculture's communes based in rural areas where a collective and horizontal way of life was experimented.

These experiences led him to think of a way to provide access to the necessary tools useful for communal living, but also to expand subjectivity through knowledge. Brand's notion of tool was therefore very wide: small-scale technologies, books, manuals, accessories. Technology and informations as means to reshape one's life and the world around.

He addressed these issues with a small-scale technology in itself: a printed catalog, published for the first time in 1968. The Whole Earth Catalog took its name and its cover picture from a previous project by Brand. In 1966 he printed buttons with the question “Why Haven't We Seen a Photograph of the Whole Earth Yet?” He was convinced that a picture of the planet would foster people to think themselves as part of one single global system. The Catalog became soon widespread and over its last issue in '72, it listed more than a thousand items.

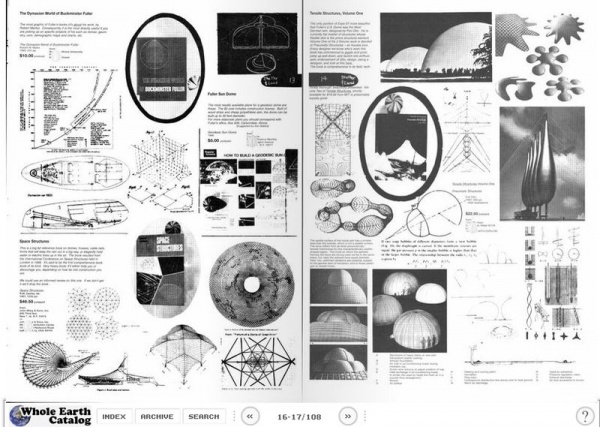

Through the Catalog's pages, the different networks whose Brand was part were ideally connected: cybernetics found place next to ecology; tents and clothes shared the page with calculators. The Catalog itself was designed according to systems theory, in fact each of the seven main categories (Understanding Whole Systems, Shelter and Land Use, Industry and Craft, Communications, Community, Nomadics, Learning) had the same importance and space. The Catalog's layout favored a non-linear fruition, the reader could find his own path through the pages because, as it was declared in in the first issue, “We can't put it together, it is together”. The editorial process completely reflected systems theory through a non-hierarchical structure: readers could review tools and share their experiences with those. In a way Brand set the initial conditions for what should function as an open and self-sustaining system.

The 1971 Last Whole Earth Catalog ends with the sentence “Stay Hungry, Stay Foolish”. Recently this motto became very popular because it was quoted by Steve Jobs during his commencement speech at Stanford in 2005. Steve Jobs described the WEC as “a sort of like Google in paperback form, 35 years before Google came along” (Jobs). Likewise Kevin Kelly, executive director of Wired, who was directly involved with the Catalog, referred to it as an early example of user generated content and a precursor of the blogoshpere. Kelly also claimed that the decline of the Catalog corresponding to the raise of the web was no coincidence (Kelly).

Making a close comparison between Google and the Catalog, it is possible to spot similarities but also crucial differences. Unlike the Catalog, Google is generalist: it doesn't provide context-related informations. Google's main criteria for selection is popularity. On the contrary, the Catalog was elitist or at least confined to a certain group of people. Apparently Google offers an improved potential for non-linear navigation, but this doesn't necessarily develop meaningful and serendipitous connections. In addition, since 2009 Google made its research engine personalized: each query is based on such criteria as our location and our previous research history. In this way our global vision is affected by our own previous interests, in a looping circle that narrows our perspective (Pariser).

The Whole Earth Catalog was definitely an enlightening form for building network and community, and a device to grasp the tangle of informations in order to find relevant materials. It was informed by cybernetics but also by low-tech and DIY. What can we learn from the Catalog when Google and social media become generalized, all-and-nothing environments, even restricted on the basis of our previous behavior?

Nowadays the most valuable aspect of the Catalog's experience is its autonomy. Building a network outside of mainstream circuits becomes crucial when a form of independence is necessary. The Catalog is strongly related to the archive as an active practice. New meanings and relationships are defined by a conscious and dialogical cataloging. This cataloging of tools in a broad sense corresponds to an appropriation. In this way a new perspective is built and consequently a different set of values is established. From this point of view the networked classification has a profoundly ethical meaning.

Radical software, printed matter as distributed opposition

The Whole Earth Catalog opened the doors for a completely new approach to publishing. Many followed its example, both in terms of content, publishing model and in terms of design. Some of the produced magazines became, in turn, a source of inspiration for Brand and his crew. In the September’s issue of the WEC, a review by Stewart Brand himself said: “We get letters–saying how encouraging, enspiriting, possibility-expanding the Whole Earth Catalog is […] Well, it’s how I feel about Radical Software.” (Brand, p.34)

Radical Software was the main project by the RainDance Corporation, founded in the summer of 1969 by the artist and activist Frank Gillette. The collective’s name was an ironic reference to Rand Corporation, a very powerful american think tank. The scope of RainDance was to rethink and democtratize media. People with diverse backgrounds were involved in it: for instance Micheal Shamberg, a former journalist for Time; Ira Schnieder, scientist devoted to filmmaking; Louis Jaffe, musician and photographer. All members shared an interest in videotape and television, very often accompained by an active practice. Videotapes and installations were seen as means for social change, strategies to oppose the control and one-way flow of information of television.

In the editorial of the first issue it was affirmed that in the technological environment “there is too much centralization and too little feedback” (Radical Software, p.1). These words clearly echo Steward Brand’s mentors: Norbert Wiener, Buckminster Fuller and Marshall McLuhan. According to them, technology should be read in ecological terms: it is not originally evil, it was only been misused by the technocratic bureaucracy.

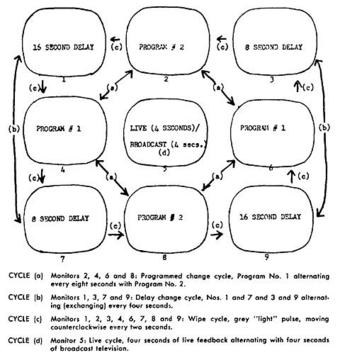

These ideas were expressed through an early interactive installation by Gillette and Schneider, originally shown at the Exhibition “TV as a Creative Medium” in 1969. Wipe Cycle consisted of nine screens placing the viewer in the context of the information overload, demonstrating in this way that the spectator is a bit of information in itself. Another project never accomplished bringing this ideas about was called The Center for Decentralized Television.

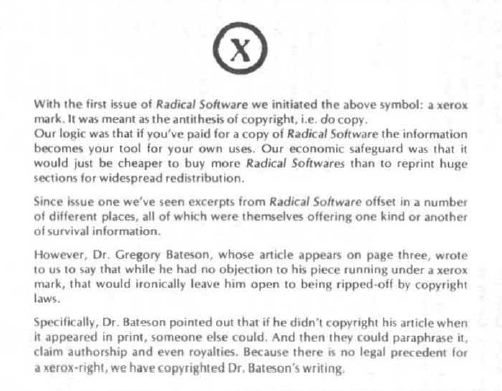

Radical software was born out of the Video Newsletter, whose objective was to connect the several realities of independent video. It included eleven issues published between 1970 and 1974. The reflection on technology was also expressed through the dissemination strategy. Instead of the traditional copyright, Radical Software coined a brand new mark characterized by a circle with an X in the middle. The X was for Xerox which meant “Do Copy”. Each issue contained a section called “Feedback”, in which artists, writers, groups and collectives could publish announcements.

From the fourth issue, the decentralizing potential of the magazine is completely expressed “farming out” big parts of it to other collectives. In this way RainDance solved a problem of resources –Radical Software required a heavy engagement which didn’t leave enough time to the artistic practice– while strenghtening the relationship among geographically dispersed entities.

As for the Whole Earth Catalog, the design of the magazine was directly influenced by the contents. Through a DIY approach, it mashed up technical charts, psychedelic drawings and underground comics. Often the text layout was in form of flow chart referring this way to programming and electronics.

The main difference between Whole Earth Catalog and Radical Software was ideological: while the former aimed to build a new form of civilization, the latter questioned the current hierarchies.

Conclusion

Nowadays virtual communities are often purposeless, not driven by a specific aim. Instant sharing decontextualizes contents and limits the appropriation of those. Each one of the experiences previously explored suggest a response to the current circumstances. They drive us to focus on the relation we establish with digital systems through actions that we often perform unconsciously. It is worthwhile to rethink the dinamics of constituiting a network as they appear standardized and stiffened by the mainstream digital platforms. An active and meaningful sharing discourse is desirable, because it allows to determine what is valuable out of a specific context.

Punch cads punched with words, from the phonogram album cover for "FSM's Sounds and Soungs of the Demonstration!"

Back cover of the Last Whole Earth Catalog, 1971.

Spreads from the Whole Earth Catalog

Wipe Cycle's installation scheme

Radical Software Issue 1, front cover.

Radical Software Issue 3 p. 1, "Do copy" symbol.

- Gigliotti D. (2003) ”A Brief History of RainDance". [online], Available: http://www.radicalsoftware.org/e/history.html.

- Hayles K. (1999). Virtual bodies and flickering signifiers, in How we became posthuman:virtual bodies in cybernetics, literature and informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Jobs S. (2005), Commencement Speech at Stanford University, June 12, 2005, [online], Available: http://news.stanford.edu/news/2005/june15/jobs-061505.html

- Joselit D. (2007) Feedback: Television against Democracy, Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Kelly K. (2008), “The Whole Earth Blogalog”, [online], Available: http://kk.org/ct2/2008/09/the-whole-earth-blogalog.php

- Lubar S. (1992) 'Do Not Fold, Spindle Or Mutilate: A Cultural History Of The Punch Card', Journal of American Culture, Winter, pp. 43- 55.

- Pariser E. (2011), The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You, Penguin Press

- Turner F. (2006), From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism.

- Radical Software, Issue 1, 1970.

- Brand S. (1970), "Radical Software", in Whole Earth Catalog, September 1970.

- Radical Software's archive [online] Available: http://www.radicalsoftware.org/

- Whole Earth Catalog's archive [online] Available: http://www.wholeearth.com/